Will Big Data Make IT Infrastructure Sexy Again?

Ah, big data. All of that information from mobile devices, social websites, interconnected sensors, and the Industrialized Internet of smart machines is tantalizing—especially since it means a renaissance in IT spending.

A steam train (source: Wellcome Library)

A steam train (source: Wellcome Library)

Moore’s Law Meets Supply and Demand

Love it or hate it, big data seems to be driving a renaissance in IT infrastructure spending. IDC, for example, estimates that worldwide spending for infrastructure hardware alone (servers, storage, PCs, tablets, and peripherals) will rise from $461 billion in 2013 to $468 billion in 2014. Gartner predicts that total IT spending will grow 3.1% in 2014, reaching $3.8 trillion, and forecasts “consistent four to five percent annual growth through 2017.” For a lot of people, the mere thought of all that additional cash makes IT infrastructure seem sexy again.

Big data impacts IT spending directly and indirectly. The direct effects are less dramatic, largely because adding terabytes to a Hadoop cluster is much less costly than adding terabytes to an enterprise data warehouse (EDW). That said, IDG Enterprise’s 2014 Big Data survey indicates that more than half of the IT leaders polled believe “they will have to re-architect the data center network to some extent” to accommodate big data services.

The indirect effects are more dramatic, thanks in part to Rubin’s Law (derived by Dr. Howard Rubin, the unofficial dean of IT economics), which holds that demand for technology rises as the cost of technology drops (which it invariably will, according to Moore’s Law). Since big data essentially “liberates” data that had been “trapped” in mainframes and EDWs, the demand for big data services will increase as organizations perceive the untapped value at their fingertips. In other words, as utilization of big data goes up, spending on big data services and related infrastructure will also rise. “Big data has the same sort of disruptive potential as the client-server revolution of 30 years ago, which changed the whole way that IT infrastructure evolved,” says Marshall Presser, field chief technology officer at Pivotal, a provider of application and data infrastructure software. “For some people, the disruption will be exciting and for others, it will be threatening.”

For IT vendors offering products and services related to big data, the future looks particularly rosy. IDC predicts stagnant (0.7%) growth of legacy IT products and high-volume (15%) growth of cloud, mobile, social, and big data products—the so-called “3rd Platform” of IT. According to IDC, “3rd Platform technologies and solutions will drive 29 percent of 2014 IT spending and 89 percent of all IT spending growth.” Much of that growth will come from the “cannibalization” of traditional IT markets.

Viewed from that harrowing perspective, maybe “scary” is a better word than “sexy” to describe the looming transformation of IT infrastructure.

Change Is Difficult

As Jennifer Lawrence’s character in American Hustle notes, change is hard. Whenever something new arrives, plenty of people just cannot resist saying, “It’s no big deal, nothing really different, same old stuff in a new package,” or words to that effect. And to some extent, they’re usually right—at least initially.

Consider the shift from propellers to jet engines. A jet plane looks very similar to a propeller-driven plane—it has wings, a fuselage, a tail section, and the same basic control surfaces. But the introduction of jet engines completely transformed the passenger aviation industry by allowing planes to fly higher, faster, longer, and more cost effectively than ever before. The reason we don’t think twice about stepping into airliners is largely because of jet engines, which are significantly more reliable—and much quieter—than propellers.

Two or three years ago, when you asked a CIO about data, the standard reply was something like, “Don’t worry, we’re capturing all the data we create and saving it.”

Here are the sobering realities: no databases are big enough and no networks are fast enough to handle the enormous amounts of data generated by the combination of growing information technologies such as cloud, mobile, social, and the infelicitously named “Internet of Things.” A new push by large companies toward “zero unplanned downtime,” a strategy that depends on steady flows of data from advanced sensors, will undoubtedly contribute to the glut.

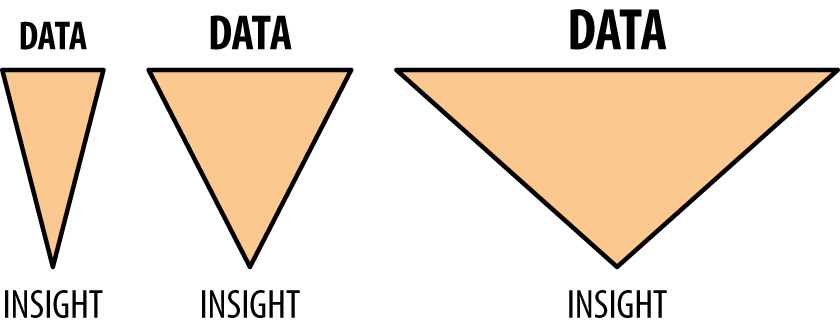

If we conceptualize the relationship between data and insight over the past three decades, it looks something like the following figure.

Obviously, the funnels are not drawn to scale, but you get the idea. The mouth of the funnel keeps getting wider to accommodate greater amounts of data, while the spout of the funnel at the bottom remains narrow. At what point does it stop making sense to keep throwing data into the top of the funnel?

Let’s say that for a variety of reasons (mostly legal and regulatory), we decide to keep collecting as much data as we possibly can. How are we going to manage all of that new data and where will we put it? The answer is deceptively simple: not all of that new data will be sent back to a data warehouse and saved; most of it will be evaluated and analyzed closer to its point of origin. Throw away the funnel model—more decisions will be made at the edges of systems, by smart devices and increasingly by smart sensors, which are all part of the new and expanding universe of IT infrastructure.

Fred Thiel is an IT industry expert, serial entrepreneur, and advisor to private equity and venture capital firms. He offers this scenario illustrating how the intersection of big data and the Internet of Things will lead to substantial changes in IT infrastructure:

- You have a pump operating somewhere. The pump is equipped with a sensor that’s connected to a data gateway at the edge of a data network. And you know that, compared to ambient temperature, the operating temperature of the pump should be X, ±10%. As long as the pump operates within its parametric norm, the system that listens to it and monitors its performance isn’t going to report any data. But the minute the pump’s temperature or performance breaks through one of its parametric norms, the system will report the event and give you a log of its data for the past 30 seconds, or whatever time interval is appropriate for the system.

Now imagine that scenario playing out all over the world, all the time, in every situation in which data is being generated. Instead of infrastructure that’s engineered to capture data and send it back to a data center, you need infrastructure engineered to capture data and make choices in real time, based on the context and value of the data itself.

That kind of infrastructure is a far cry from the traditional IT infrastructure that was basically designed to help the CFO close the company’s book faster than the manual accounting systems that preceded IT. It’s easy to forget that, for many years, IT’s primary purpose was to automate the company’s accounting processes. A surprising number of those original systems are still kicking around, adding to the pile of “legacy spaghetti” that CIOs love to complain about.

What we’re witnessing now, however, is a somewhat bumpy transition from the old kind of IT that faced mostly inward, to a new kind of IT that mostly faces outward. The old IT dealt mostly with historical information, whereas the new IT is expected to deal with the realities of the outside world, which happens to be the world in which the company’s customers and business partners live. Another way of saying this is that after years of resistance, IT is following the nearly universal business trend of replacing product-centricity with customer-centricity.

An extreme example of this trend is bespoke manufacturing, in which Henry Ford’s concept of an assembly line turning out millions of the exact same product is stood on its head. In bespoke manufacturing, product development isn’t locked into a cycle with a beginning, middle, and end. Product development is iterative and continuous. Cutting-edge processes such as 3D printing and additive manufacturing make it possible to refine and improve products ad infinitum, based on user feedback and data sent back to the manufacturing floor by sensors embedded in the products.

Jordan Husney is strategy director for Undercurrent, a digital strategy firm and think tank. His interests include “extending the digital nervous system to distant physical objects,” and he provides advisory services for several Fortune 100 companies. From his perspective, the challenge is rapidly scaling systems to meet unexpected levels of demand. “I call it the ‘curse of success’ because if the market suddenly loves your product, you have to scale up very quickly. Those kinds of scaling problems are difficult to solve, and there isn’t a universal toolkit for achieving scalability on the Internet of Things,” he says. “When Henry Ford needed to scale up production, he could add another assembly line.”

In modern manufacturing scenarios, however, finished products are often assembled from parts that are designed and created in multiple locations, all over the world. When that’s the case, it’s more important to standardize the manufacturing processes than it is to standardize the parts. “The new edge for standards isn’t the part itself, it’s the process that makes the part,” says Jordan. “That type of approach, as manufacturing becomes increasingly bespoke, is going to ripple backward through the organization. The organization is going to have to be on its toes to handle that new kind of standard, in which the process is the standard, not the final product.”

The future of fabrication will involve increasingly seamless integrations of digital and mechanical technologies. “Imagine a team that’s designing a new part for a complex machine and while they’re designing the part, every time their design application automatically saves a file, the file is sent into the cloud and evaluated by an application that automatically calculates the cost of producing the part, the time required to produce it, and the feasibility of producing it,” says Jordan. Any segment of the design that is judged infeasible or uneconomical will be highlighted, in real time, by the team’s design application. “If we look at that scenario from an IT perspective, we really have to consider whether we have the IT infrastructure necessary to make that future possible.”

The new modes of iterative manufacturing and bespoke fabrication will require IT infrastructure that connects and orchestrates interactions between smarter devices, smarter networks, and smarter sensors. The table stakes, it would seem, have gone up.

Meanwhile, Back at the Ranch…

Mike Olson is the founder and chief strategy officer of Cloudera, an early champion of Hadoop for enterprise users and a leading provider of analytic data management services. In many ways, Mike’s story is similar to the stories of other highly successful tech entrepreneurs. But it tracks nicely with the emerging narrative of how big data is transforming IT infrastructure. At Berkeley, Mike studied under the legendary Michael Stonebraker, whose research was critical to the development of modern relational database systems. After leaving Berkeley, Mike spent the next couple of decades building database products. He helped launch a series of successful tech firms and made good money in the process. “We built great products, but it wasn’t like you woke up with your heart pounding. Over those decades, relational databases just became the default answer to any kind of data management problem,” says Mike.

While Mike was building relational databases for big companies, Google was dealing with its own unique data challenge. Google’s mission was to vacuum up all the available data on the Web, index it, and make it searchable. Accomplishing that mission required a new approach to data management, something that went far beyond the abilities of relational database technology. Google’s solutions were GFS (Google File System) and MapReduce, which was essential to the subsequent development of Hadoop. “In 2004, Google published a couple of papers about GFS and MapReduce, and most of us in the relational database industry thought it was a joke. We totally disregarded it,” Mike recalls. “It didn’t use SQL, which we knew was crucial to data management. What we didn’t know was that Google wasn’t trying to build a database system that solved the same problems as ours did. Google was building a system that addressed a new problem, at a new scale, and handled complex data from many different sources.”

Four years later, Mike and some of his friends revisited Google’s research and saw the potential for creating a new industry based on Hadoop. Their driving force was big data—back in 2004, only Google and a handful of other companies were focused on solving big data problems. By 2008, big data had become more widely understood as a serious challenge (or opportunity, depending on your perspective) for organizations worldwide. Machine-to-machine interactions were creating huge volumes of new data, and at astonishing speeds. Suddenly, database managers and database providers were in the hot seat.

Mike describes the transition: “In the old days, when you wanted to build a data center, you called Sun Microsystems and you ordered the biggest box they had. They’d ship it to you as a single centralized server. Then you’d take whatever money you had left over and send it to Oracle, and they’d sell you a license to run their database software on the box. That’s where you put all of your data. But machine-generated data grows faster than any box can handle. A single, centralized system can’t scale rapidly enough to keep up with all the new data.”

Google perceived that an entirely new approach to database management was necessary. “They took what were essentially a bunch of cheap pizza boxes and created a massively parallel infrastructure for managing data at scale. That was Google’s genius, and it’s changed the way we build data centers, forcing us to design new data management architectures for large enterprises.”

Throwing Out the Baby with the Bathwater?

There is a difference of opinion over the extent to which newer data management systems based on open source Hadoop will replace or augment traditional systems such as those offered by Microsoft, IBM, and Oracle.

Abhishek Mehta is founder and CEO of Tresata, a company that builds analytic software for Hadoop environments. From his perspective, HDFS (Hadoop distributed file system) is the future of data management technology. “HDFS is a complete replacement for not just one, but four different layers of the traditional IT stack,” says Abhi. “The HDFS ecosystem does storage, processing, analytics, and BI/visualization, all without moving the data back and forth from one system to another. It’s a complete cannibalization of the existing stack.”

He predicts that companies without HDFS capabilities will find themselves lagging behind Hadoop-equipped competitors. “The game is over and HDFS has won the battle,” says Abhi. “The biggest problem we see is companies that haven’t made HDFS a core part of their IT infrastructure. Not enough companies have HDFS in production environments. But here’s the good news: They have no choice. The economics of the traditional systems no longer make sense. Why pay $10,000 per terabyte to store data when you can pay much less? There’s a reason why dinosaurs are extinct.”

Jorge A. Lopez is director of product marketing at Syncsort, a software firm specializing in data integration. Founded in 1968 by graduates of New York University and Columbia University, Syncsort develops products and services for Hadoop, Windows, UNIX, Linux, and mainframe systems. “We don’t recommend throwing out the baby with the bathwater,” says Jorge. “Organizations have spent the past decade building up their architectures. But increasing volumes of data create new tensions, and as a result, organizations are weighing tradeoffs.”

In business there is an old saying: “You can have it fast, you can have it good, you can have it cheap. Pick two.” As the volume, velocity, and variety of big data continue to climb, something’s gotta give. “If your costs are growing at the same pace as your data, that’s a huge problem. If your costs are growing faster than your data, it becomes economically impossible to keep up,” says Jorge. Hadoop gives companies a wider range of choices when making tradeoffs. “You can shift workloads from your mainframe to Hadoop, which reduces or defers your costs and also lets you start building the skills within your IT organization that will be essential in the future,” says Jorge. “You save a ton of money, and you address the skills gap, which is becoming a really serious issue for many companies.”

In the scenario described by Jorge, ETL (extract, transform, load) is the low-hanging fruit. The money you save by shifting ETL workloads from traditional systems into HDFS could be invested in research, product development, or new infrastructure. “Don’t get me wrong, I’m not saying that now you can get rid of your Teradata implementation. But ETL uses a large percentage of your Teradata resources and it doesn’t add value. If you shift that workload to Hadoop, you have free capacity in your Teradata box and you can do work that adds real value,” says Jorge. “To me, a sign that Hadoop is maturing is that big companies in retail, finance, and telecommunications are looking at Hadoop as a way of saving mainframe costs and leveraging data that was previously unusable. Believe it or not, lots of those companies still use tape to store data, and once it’s been formatted for tape, the data becomes very difficult to access.”

For people of a certain generation, tape drives were sexy—along with hula hoops, marble ashtrays, and Brigitte Bardot.

“It’s not that the old architecture wasn’t sexy, it’s that the new architecture creates very tangible value in terms of being able to draw insights from data in a variety of ways,” says Jim Walker, director of product marketing at Hortonworks, an early leader in the Hadoop movement. “We’re re-architecting the data center so we can interact with it in multiple different ways simultaneously. It’s the whole concept of schema-on-read as opposed to schema-on-write that’s transforming the way we think about queries and the way we provide value to the enterprise with data.”

For big data evangelists, what’s sexy about new IT infrastructure is its potential for delivering insights that lead to better—and more profitable—business decisions. Delivering those kinds of value-added insights requires IT systems that allow users to ask a much more varied set of questions than they can today. “We’re maturing toward a contextual-query model. We’re definitely still far away from it, but we’re setting the IT infrastructure in place that will make it possible,” says Jim. “That’s what it’s really all about.”

API-ifiying the Enterprise

Greater accessibility of data at significantly lower costs sounds like a solid argument in favor of modernizing your IT infrastructure. But wait, there’s more. As Jorge Lopez suggested earlier, big data technologies also create opportunities for learning new skills and transforming the culture of IT.

Rick Bullotta is cofounder and CTO at ThingWorx, an application platform for the Internet of Things. From his perspective, big data isn’t merely transforming IT infrastructure—it’s transforming everything. “Not only do we have to change the infrastructure, we have to fundamentally change the way we build applications,” says Rick. “Hundreds of millions of new applications will be built. Some of them will be very small, and very transient. Traditional IT organizations—along with their tooling, approaches, and processes—will have to change. For IT, it’s going to be a different world. We’re seeing the ‘API-ification’ of the enterprise.”

Traditional software development cycles taking 3 to 18 months (or even longer) are simply not rapid enough for businesses competing in 21st-century markets. “Things are happening too fast and the traditional approach isn’t feasible,” says Rick. “IT isn’t setup for handling lots of small projects. Costs and overhead kill the ROI.” Traditional IT tends to focus on completing two or three multimillion-dollar projects annually. “Think of all the opportunities that are lost. Imagine instead doing a thousand smaller projects, each delivering a 300 percent ROI. They would generate an enormous amount of money,” says Rick.

The key, according to Rick, is “ubiquitous connectivity,” which is a diplomatic way of saying that many parts of the enterprise still don’t communicate or share information effectively. The lack of sharing suggests there is still a need for practical, realtime collaboration systems. Dozens of vendors offer collaboration tools, but it’s hard to find companies that use them systematically.

The idea that critical information is still trapped in silos echoes throughout conversations about the impact of big data on enterprise IT. Sometimes it almost seems as though everyone in the world except IT intuitively grasps the underlying risks and benefits of big data. Or can it be that IT is actively resisting the transformational aspects of big data out of irrational fears that big data will somehow upset longstanding relationships with big vendors like IBM, Microsoft, and Oracle?

Beyond Infrastructure

William Ruh is vice president of GE’s software and analytics center. Before joining up with GE, he was a vice president at Cisco, where he was responsible for developing advanced services and solutions. In a very real sense, he operates at the bleeding edge, trying to figure out practical ways for commercializing new technologies at global scale. When you’re on the phone with Bill, you feel like you’re chatting with an astronaut on the International Space Station or a deep-sea diver exploring the wreckage of a long-lost ship.

From Bill’s perspective, transforming IT infrastructure is only part of the story. “I think we all understand there’s a great opportunity here. But it’s not just about IT. This is really where IT meets OT—operational technology. OT is going to ride the new IT infrastructure,” he says.

IT is for the enterprise; OT is for the physical world of interconnected smart machines. “Machines can be very chatty,” says Bill. “You’ll have all of those machines, chatting among themselves in the cloud, pushing out patches and fixes, synchronizing and updating themselves—it will be asset management on steroids.”

In the world of OT, there is no downtime. Everything runs 24/7, continuously, 365 days a year. “People get irritated when their Internet goes down, but they get extraordinarily upset when their electricity fails,” says Bill. The role of OT is making sure that the real world keeps running, even when your cell phone drops a call or your streaming video is momentarily interrupted.

OT is enabled by the Industrial Internet, which is GE’s name for the Internet of Things. Unlike the Internet of Things, which sounds almost comical, the Industrial Internet suggests something more like the Industrial Revolution. It evokes images of a looming transformation that’s big, scary, and permanent.

That kind of transformation would not necessarily be bad. Given the choice, most of us would take the 21st century over the 18th century any day. There will be broad economic benefits, too. GE estimates the “wave of innovation” accompanying the Industrial Internet “could boost global GDP by as much as $10–15 trillion over the next 20 years, through accelerated productivity growth.” IDC projects the trend will generate in the neighborhood of $9 trillion in annual sales by the end of the decade. On the low end, Gartner predicts a measly $1.9 trillion in sales and cost savings over the same period.For an excellent overview, read Steve Johnson’s article in the San Jose Mercury News, “The ‘Internet of Things’ could be the next industrial revolution.”

Economic incentives, whether real or imagined, will drive the next wave of IT transformation. It’s important to remember that during the Industrial Revolution, factory owners didn’t buy steam engines because they thought they were “cool.” They bought them because they did the math and realized that in the long run, it made more economic sense to invest in steam power than in draft animals (horses, oxen, etc.), watermills, and windmills.

Not everyone is certain that IT is prepared for transformation on a scale that’s similar to the Industrial Revolution. In addition to delivering service with near-zero latency and near-zero downtime, IT will be expected to handle a whole new galaxy of security threats. “When everything is connected, it ups the ante in the cyber security game,” says Bill. “It’s bad enough when people hack your information. It will be worse when people hack your physical devices. The way that IT thinks about security has to change. We can’t go with the old philosophy in the new world we’re building.”

Can We Handle the Truth?

If problems such as latency, downtime, and security aren’t daunting enough, Mike Marcotte offers another challenge for data-driven organizations: dealing with the truth, or more specifically, dealing with the sought-after Holy Grail of data management, the “single version of the truth.”

Mike is the chief digital officer at EchoStar, a global provider of satellite operations and video delivery solutions. A winner of multiple Emmy Awards, the company has pioneered advancements in the set-top box and satellite industries and significantly influenced the way consumers view, receive, and manage TV programming.

As a seasoned and experienced IT executive, Mike finds the cultural challenges of new infrastructure more interesting than the technical issues. “The IT systems are fully baked at this point. The infrastructure and architecture required to collect and analyze massive amounts of data work phenomenally well. The real challenge is getting people to agree on which data is the right data,” says Mike.

The old legacy IT systems allowed each line of business to bring its own version of the truth to the table. Each business unit generated a unique set of data, and it was very difficult to dispute the veracity of someone else’s numbers. Newer data management systems, running on modern enterprise infrastructure, deliver one set of numbers, eliminate many of the fudge factors, and present something much closer to the raw truth. “In the past, you could have 200 versions of the truth. Now the architecture and the computing platforms are so good that you can have a single version of the truth. In many companies, that will open up a real can of worms,” he says.

In a tense moment near the end of A Few Good Men, the commanding officer played by Jack Nicholson snarls, “You can’t handle the truth!” Was he right? Can we handle the truth, or will it prove too much for us? Driven by the growth of big data, is our new IT infrastructure the path to a better world, or a Pandora’s Box? The prospects are certainly exciting, if not downright sexy.